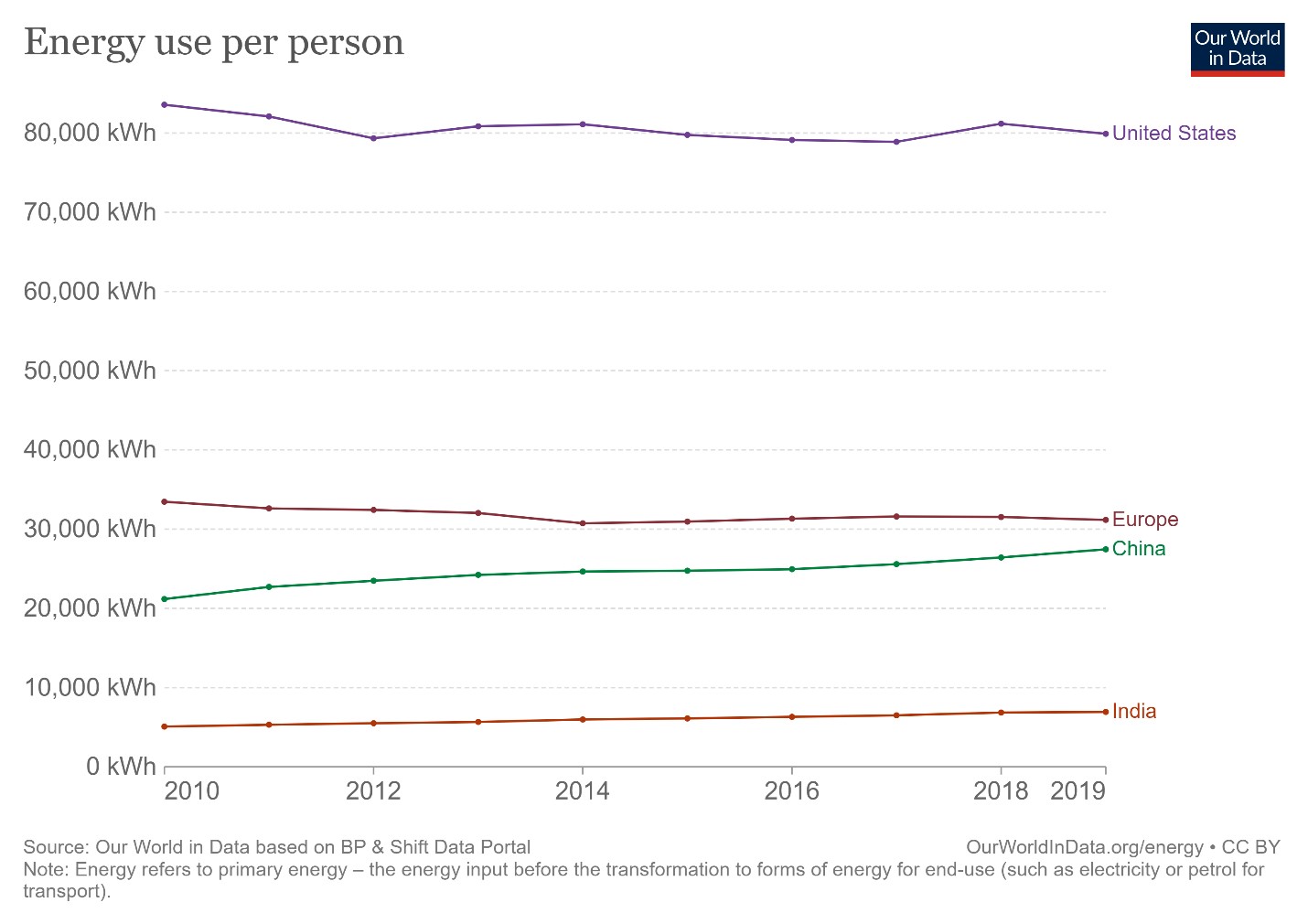

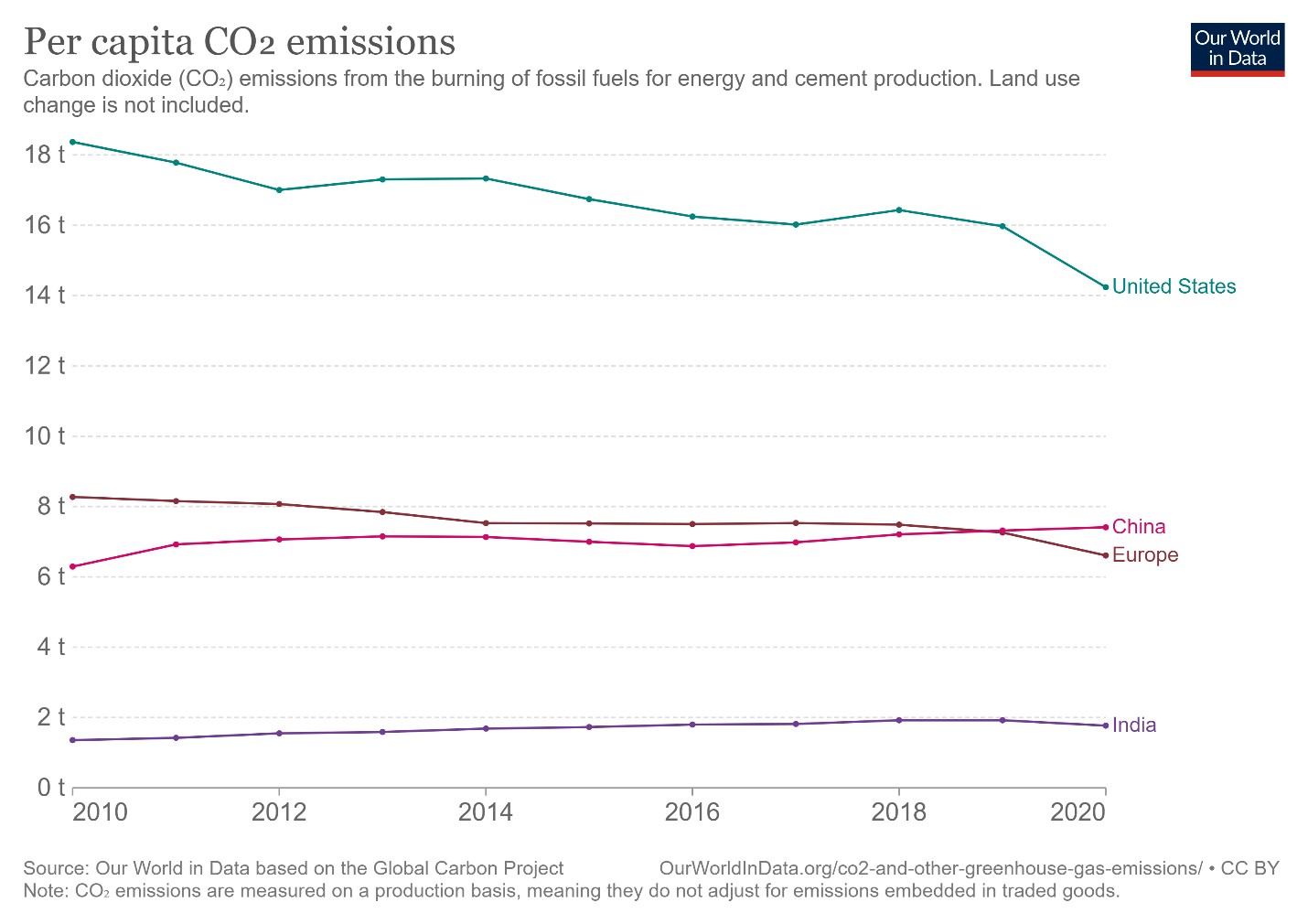

COP26 has once again placed the United States front and center regarding the global focus to reduce emissions. As of today, the United States remains the second largest emitter of CO2 and the largest of the populous countries on a per capita basis. That being said, emissions in the United States have come down significantly, in total and even more so per capita, over the last few years and global warming has now become a major topic of public debate.

In order to support the COP26 targets, a continued substantial reduction of emissions is necessary. While there is no broad support in the population to sacrifice economic interests of the United States as long as other countries continue to expand thermal generation, there is definitely increased sensitivity, and there is financial pressure from the investor community.

In order to support the COP26 targets, a continued substantial reduction of emissions is necessary. While there is no broad support in the population to sacrifice economic interests of the United States as long as other countries continue to expand thermal generation, there is definitely increased sensitivity, and there is financial pressure from the investor community.

Currently energy prices (electricity, heating, fuel) are high. The reasons for this special situation are complex and range from temporary supply demand imbalances resulting from substantial changes in production and mobility during 2020 and 2021 due to pandemic to political changes. This has created disruption, and it will take some time for markets to adjust.

Unlike the United States, Europe has a good reputation regarding its efforts to curb emissions, but it is not broadly warranted. Most recently the big winner of high energy prices in Europe has been coal. While the governments were discussing at COP26 what to do, electricity generation from coal increased. The reason is simple, natural gas prices are high, coal is plentiful and coal fired power plants became highly lucrative again.

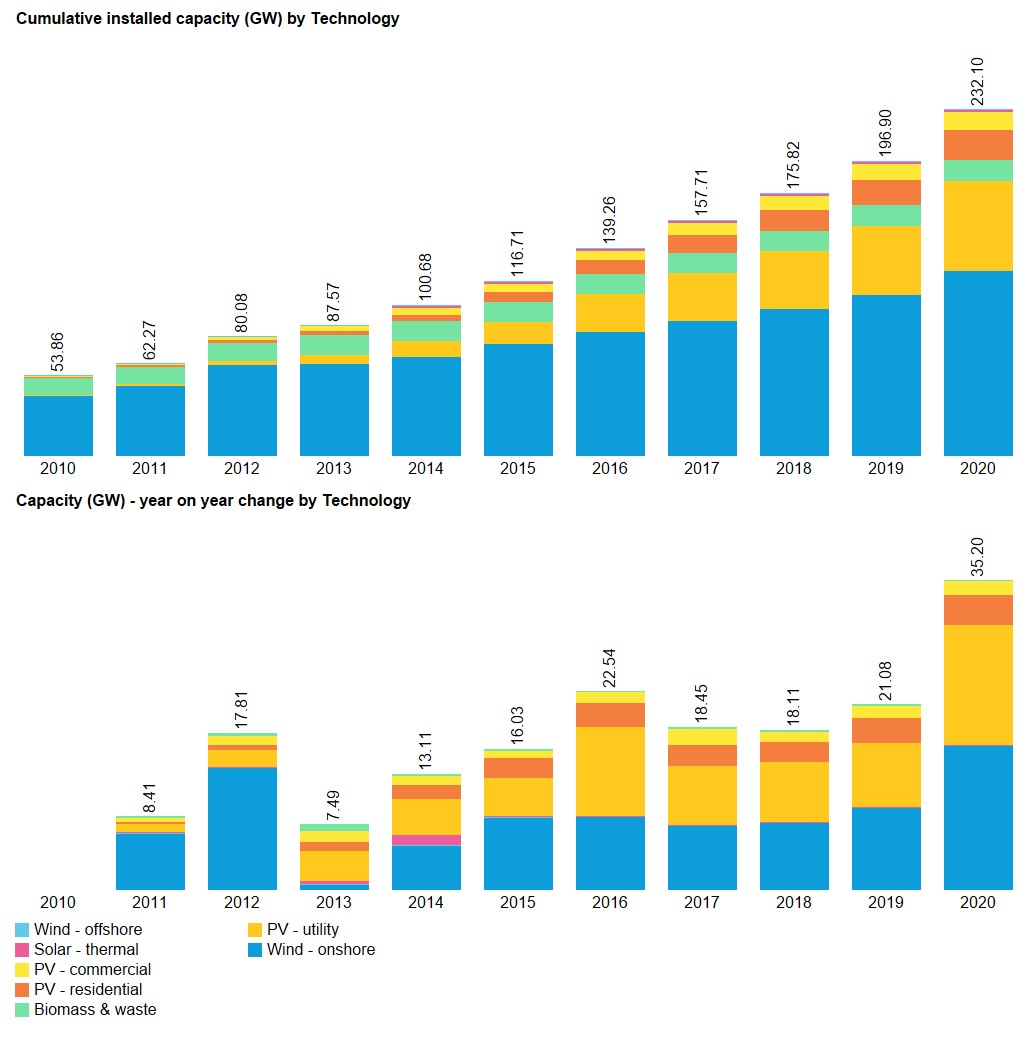

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

As it relates to renewable energy generation, the international reputation of the United States is far worse than the reality. Despite the pandemic, 2020 was a record year of new installations for both wind and solar PV, while electricity generation from coal has dropped significantly during the last few years. The United States has a leading position for wind and solar in the world, and the substance is even better than what those numbers indicate, because the average capacity factor of wind and solar plants in the United States is higher than in Europe. The generation of electricity from renewable energy sources continues to grow, but given the modest capacity factors of wind and solar compared to thermal power, the percentage of renewable energy generation is far below the percentage of renewable energy installed capacity. It takes on average more than 5 times the capacity when replacing thermal generation with solar.

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

The growth of renewables in the United States is in large part attributable to a system of direct and indirect subsidies that far exceed what has been available in other developed countries.

The two primary direct subsidies are the Production Tax Credit (“PTC”) and the Investment Tax Credit (“ITC”). The PTC was enacted during the George H.W. Bush administration in 1992, and it provides a tax credit for every kWh produced and sold over 10 years. It is applicable to a large number of technologies but primarily used for onshore wind farms with high capacity factors. At the full level, the PTC contributed more than 65% of the cost of a wind farm to an acquiring investor. The ITC was enacted during the George W. Bush administration in 2005 and it provides a tax credit for a portion of its eligible cost. It is applicable to a large number of technologies but primarily used for solar plants given the low capacity factor, and will also be used for offshore wind given the high cost vs capacity factor. As of 2021, the PTC is at USD 0.018/kWh (60% of the full level) and the ITC is at 26% of eligible cost (reduced from 30%). Under current legislation implemented in 2016 during the Barack Obama administration, both tax credits are being phased out over the next few years to avoid a regulatory cliff. However, the phase-out of the ITC and PTC was deferred by 3 years in 2020 under the Donald Trump administration.

In addition, there are many indirect subsidies, mostly at state level. The two primary ones are the renewable portfolio standard (“RPS”) and net metering regulations. There is a RPS in 31 states, and another 7 state have renewable portfolio goals, and it requires generators to either produce renewable energy or to acquire renewable energy certificates (“REC”), which are awarded to producers of renewable energy. In certain states the value of the RECs far exceeds the value of the electricity produced. Net metering applies in many regional markets and allows an electricity consumer that has installed a renewable energy facility at its site to feed excess generation over its own consumption into the grid at favorable rates. It still widely applies throughout the country, and is largely used for solar plants, but the concept is not viable on the long run as it is based on arbitrage against the cost of utility provided infrastructure.

While it is difficult to make exact comparisons, there is plenty of evidence that the United States has subsidized renewable energy more than any other country. The problem has been and remains the complex nature of the direct and indirect subsidies. To benefit from tax credits, investors without sufficient own taxable income, which also includes tax-exempt parties such as pension plans, need to enter into complex tax equity transactions. The ITC creates a moral hazard given that higher costs lead to higher subsidies. This remains one the key reasons why solar plants cost much more in the United States than other developed countries. REC markets are very volatile given the dependency on state level RPS that can change quickly. Financing is more expensive than in Europe due to the more complex structures. The substantial inefficiencies of the various subsidies all create increased costs and allow certain market participants disproportional gains, rather than benefitting the consumer.

The good news is that the United States renewable energy market continues to grow. In many local markets, the levelized cost of energy (“LCOE”) from renewable energy sources is competitive when compared to traditional power plants. The outlook for the sector remains very positive, but there are impediments. The United States is a very large country, and the wind and solar resources are not always where the need for electricity is. The power markets are not fully interconnected and transmission capacity is limited. To make a quantum leap, infrastructure needs substantial upgrading. The inherent problem of wind and solar generated electricity is to match the only partially predictable production with consumption. This is only possible with more redundancy in the transmission system and the ability to balance out differences. Balancing can occur by quickly mobilizing dispatchable generation and through efficient means of storage. Batteries are suitable to shift load at solar plants, to address frequency modulation and to offset spikes, but not viable to balance out large wind farms. That requires substantial capacity from fast reacting power plants. In regions without major hydroelectric storage plants, that can only be achieved with gas fired power plants for shortfalls, and the production of green hydrogen for surplus storage. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted on November 15, 2021, includes certain renewable energy aspects, but more importantly USD 65bn for transmission upgrades and USD 8b for 4 green hydrogen hubs. That could give the industry a jump start.

Fundamental changes in the generation of electricity alone will not be sufficient to reduce emissions as needed. It is critical to also reduce consumption and increase efficiency. In that regard, the United States are behind most developed nations.

The reasons are multifaceted, and culture and consumer behavior are critical components. There is a sense of entitlement to be wasteful. It starts on a very basic level. While a European or Asian will switch off the light in a room when leaving it, doing so is not common in the United States. There is limited sensitivity to usage and there is limited regulation. This applies to electricity, heat, water, waste, etc. Consumer focus remains on initial cost, rather than lifetime cost. There is also no regulatory focus on disclosure, whether for appliances or a residence, and most HVAC systems are outdated. Mandating increased efficiency for residential heating systems, which are largely oil and gas based, would be easy for local authorities as part of the permit process for new buildings. While there is some energy efficiency allocation in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, it is comparably small. It may well be easier and cheaper to reduce emissions through reduced consumption and increased efficiency than through a massive change in the generation pool. There is substantial potential to simply reduce wasteful consumption and to substantially increase efficiency. This includes the use of waste products such as waste to energy, rather than the still common use of landfills; capture of fracking gas rather than flaring; use of waste biomass, which is plentiful, in biomass and biogas plants; more combined heat and power plants. There is also potential from district heating, improved building insulation, efficient home heating systems and the use of solar thermal panels for hot water, waste water management processes; etc. The key to unlocking the potential is a combination of regulatory action forcing compliance with higher standards, and finding a way to influence consumer behavior in order to create social pressure. Given the stark differences between the states, it might well fall on states to spearhead energy efficiency initiatives.

The conclusion is that it needs a multi-pronged approach to significantly reduce emissions on a global basis. Renewable energy generation needs to be increased, and consumption needs to be reduced without significantly impairing quality of life, which can be achieved through energy efficiency. That will still not be enough as there is no realistic possibility to replace traditional thermal generation of heat and electricity with renewables in time. A number of other measures are necessary. On the short term we need to reduce methane emissions. Methane has a larger impact but does not last as long as CO2. This can be achieved by eliminating landfilling, especially when open and unprotected, limiting flaring of natural gas, and by changes in agriculture and waste water management. The benefits of eliminating landfills and improving waste management go far beyond just emissions. We also need to limit the use of low grade oil products for heating, transportation and generation of electricity. The most significant impact can be achieved by implementing strict regulations for the world’s blue ocean fleet, by eliminating oil based power plants and by phasing out oil based home heating systems. We also need to avoid the vilification of all thermal power generation and instead simply first focus on the worst polluting coal fired power plants. It will not be realistic to abolish coal fired power generation quickly, but it is possible to reduce the emissions of coal fired power plants dramatically through retrofits with scrubbers. In the developed world, clean coal can be mandated. In developing countries, this could be addressed through funding from highly developed countries and especially those that have polluted in the past. Lastly, we will need to address the two elephants in the room, nuclear power and population growth.

Author:

- Juergen Moessner, President, GLOBAL CAPITAL FINANCE

Compliments of Global Capital Finance – a member of the EACCNY.

![European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources](https://eaccny.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/eaccny-logo.png)