The EACC, in partnership with the International Property Tax Institute (IPTI), wants to keep its members up to date with the latest developments in property taxes in the USA and Europe. IPTI has put together below a selection of articles from IPTI Xtracts; more articles can be found on its website (www.ipti.org).

UNITED STATES

New York: NYC Property Tax System Cushions Near-Term Blow to Revenue

- Office values are based on lagging income and expense data

- City also phases in changes in assessed value over five years

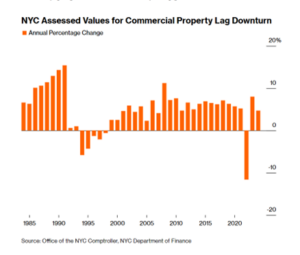

New York City’s property tax system helps explain why a “doomsday” scenario for the Manhattan office market would only result in a modest shortfall in real estate tax revenue — at least in the near term. A recent worst-case analysis by New York City Comptroller Brad Lander found that a decline of about 40% in the market value of office properties over six years would result in $1.1 billion less tax revenue for fiscal 2027, the last year of the city’s current financial plan. That represents just 3% of the projected property tax levy.

Why aren’t half-filled offices and declining rents triggering bigger revenue losses?

For one, New York doesn’t determine the value of commercial property based on recent sales. Instead, the city sets the value based on lagging income and expense information building owners submit about their properties, and phases in changes in assessed value over five years. The effect of those delays can also find precedent in the downturn in the early 1990s. “Part of the story of the city’s property tax system is that it’s got a lot of lag built into it,” said George Sweeting, former deputy director of the city’s Independent Budget Office. “All the changes get phased in and they get phased in over a fairly long period of time.”

Looking at the current fiscal year starting July 1, valuations on the city’s assessment roll are based on information filed for calendar 2021, according to a spokesman for Mayor Eric Adams. Real estate taxes are the biggest contributor to New York City’s coffers, providing about 30% of the revenue for its current year $109 billion budget. Offices account for 20% of the city’s property tax revenue and 10% of overall revenue. As businesses shift to remote or hybrid work for many jobs, the city projects office vacancies to peak at a record 22.7% this year, raising concern about the impact on tax collections. Lander’s scenario was based on a recent study by researchers at NYU Stern School of Business and Columbia University Graduate School of Business, which found that a decrease in lease revenue, renewal rates, occupancy and office rent would cut the value of office buildings in the city by 44% over the next six calendar years. Because of the gradual nature of office valuations based on net operating income, the comptroller assumes that office market values would decrease 6% annually from fiscal 2025 through fiscal 2027, with further declines until 2031. To be sure, the comptroller’s analysis doesn’t estimate the indirect impact of a drop in office occupancy on city tax revenue — such as the repercussions for commercial real estate lenders or spill over effects on restaurants and shops.

While the outlook for New York’s office market is grim, the real estate downturn of the early 1990s provides some historical perspective on risks to the city’s coffers. Back then, an oversupply of office buildings built on speculation, a deep recession and an exodus of back-office operations led to a commercial real estate bust. However, assessed values for commercial space didn’t start falling until the 1994 fiscal year. From peak to trough, assessed values fell by 13% through fiscal 1998, according to the comptroller’s report. By then, the city was in recovery, said Sweeting, currently a senior fellow at the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. “Again, you get the effect of the lags delaying the impact of economic conditions on the property tax,” said Sweeting. “Doesn’t avoid them, but they just come later.”

Illinois: Chicago has 2nd-highest commercial property taxes in U.S.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson and progressive allies said the city can find fiscal flexibility by taxing big business. The city is already home to the second-highest commercial property taxes in the nation. Chicago has the second-highest commercial property taxes in the nation at 3.78% – more than double the U.S. average for the largest cities in each state, a study found. Only Detroit has higher commercial property taxes at 4.21%, according to the study by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence. Why? The study stated Detroit has a high effective commercial property tax rate on $1 million-plus commercial properties because of low property values in the struggling city, which went bankrupt in 2013. The study found Chicago’s high rate is because of high local government spending and because the tax system shifts a higher burden to businesses.

Chicago’s commercial property taxes have been rising rapidly in recent years. In the past decade, total taxes billed have increased from $1.98 billion in tax year 2011 – payable in 2012 – to $3.82 billion in tax year 2021 – payable in 2022. That represents a 93% increase in 10 years.

Chicago commercial property taxes are already 2.5 times higher than residential property taxes because Cook County assesses commercial property at far higher values than residential property. Commercial property taxes in central Chicago now average nearly $150,000 annually, with some of the city’s largest businesses being hit with substantial increases.

Willis Tower saw an $11 million increase (+29%) in property taxes for taxes due in 2022, bringing its bill to more than $50 million annually. Prudential Plaza saw more than a $5 million increase (+24%) in property taxes due in 2022, bringing its total to over $27 million last year.

Cook County commercial property taxes are on pace to rise by $1.6 billion through 2026. With the recent passage of Amendment 1 and union-ally Brandon Johnson elected mayor, that could easily rise even higher based on calls for higher taxes and the fact Johnson will be sitting across the bargaining table from the Chicago Teachers Union peers he used to lobby on behalf of. Donations from unions made up over 90%, of Johnson’s campaign funding.

Research has shown a large share of Chicago’s commercial property taxes are simply passed on to tenants in the form of higher rents. This is particularly concerning as downtown Chicago commercial properties are facing all-time high vacancy rates. Higher property taxes mean higher rents and likely fewer tenants leasing space in the city. Commercial property owners who absorb the tax costs will see a reduced return on investment, slowing growth in the city.

Despite Johnson and his allies calling for taxes on the rich, the fact is Chicago’s taxes are already high, particularly on those deemed “high earners.” Data shows an income of $100,000, the level Johnson allies have suggested should be subjected to a new city income tax, results in actual take-home pay of just $59,505 in the Windy City. That ranks 58th out of 76 cities. Levying an additional city income tax against those earners, as Johnson allies have called for, would push Chicago even farther down the list. Workers in neighboring cities such as St. Louis, Indianapolis, Milwaukee and Lexington making $100,000 incomes have actual take-home pay much higher than Chicagoans. Taking away more income would make Chicago even less competitive or attractive for workers.

Commercial property taxes aren’t the only high taxes in Chicago. Chicago’s 911 surcharge, wireless taxes, amusement tax, soft drink tax, bottled water tax, cigarette tax, parking tax, ridesharing and homesharing fees were among the highest among other large U.S. cities as recently as 2018. The city’s total combined state and local sales tax rate was tied for second highest among major U.S. cities as of 2021.

Just like burdensome commercial property taxes, the city’s residential property tax burden has seen out-of-control growth, increasing 164% in 20 years. In that same time, average residential property tax bills climbed from $1,805 in 2000 to $3,342 in 2019. Those sharp increases have been pushing residents to their breaking point.

In recent years, surveys of residents have indicated crushing property tax burdens are driving them out of the city, contributing to the city’s population loss. The city’s population loss continued in 2022, with Chicago losing 33,000 residents, accounting for one-third of the population loss suffered by the state as a whole. Last year, only New York City lost more residents than Chicago and surveys continue to show Chicagoans citing property taxes as a major concern with 51% of residents supporting a property tax freeze in the face of a property tax levy that has doubled in the past 10 years.

A city struggling with affordability should be looking at ways to reduce burdens on residents, businesses and job creators rather than seeking new ways to tax them.

California: Implications of the Commercial Real Estate Collapse for Local Government Revenues

Over the last year, news media have run numerous stories of offices, shopping malls, and other commercial properties going into foreclosure or being sold at substantial discounts. Given local government’s reliance on property tax revenues, a collapse in commercial property values might appear to have disastrous consequences for city and county finances. But circumstances differ widely from one region to another (and even between local governments within a region), so the impact of the commercial real estate decline will vary greatly.

Among the factors we must consider when evaluating the revenue impact of lower commercial real estate valuations are, first, what proportion of revenue comes from property taxes on commercial real estate, next, how closely assessed values tracked market values before the collapse, and finally, whether and when properties will be reassessed to conform with reduced market prices more closely.

San Francisco—a city at the epicenter of the commercial property collapse—provides an example of how to evaluate these three factors.

1. Commercial Property Tax Dependency

Local government is heavily reliant on property taxes generally, but many entities diversify their revenue sources with income taxes, sales and excise taxes, and other levies, as well as non‐tax revenues.

San Francisco anticipates $6.4 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2023–24. Of this total, $4.4 billion is expected to come from tax revenues. The combined city/county government levies a variety of taxes aside from the property tax, including sales tax, hotel room tax, utility user tax, parking tax, real property transfer tax, sugar sweetened beverage tax, and a unique tax on executive pay. Property taxes are expected to contribute $2.5 billion of the $4.4 billion of anticipated tax revenue.

Since the current real estate valuation slump is only affecting certain categories of properties, it is also essential to understand how assessed value breaks down by category. According to San Francisco Assessor’s latest annual report, three major commercial property categories (office, retail and hotel) accounted for 27% of total assessments in 2021. This proportion slightly understates the share of property tax revenue derived from commercial property, because only residential property is eligible for a homeowners’ exemption. In California, this exemption is only $7,000 per owner occupied property and thus not as significant a factor as in Texas.

Overall, San Francisco’s commercial property valuation decline places at risk about $700 million of annual revenue or about 11% of total general fund collections. It is easy to see how this proportion might vary across cities and counties. Suburban communities that are primarily residential are likely to have very little exposure to commercial valuations, while cities hosting large malls and office clusters should be at greater risk.

2. Assessed Versus Market Values

Due to Proposition 13, the relationship between properties assessed and market value is complex. The 1978 measure limited assessment increases to 2% annually if a property does not change hands and is not subject to major construction. For properties that have not been reassessed since Proposition 13’s implementation, their market values have risen about ten‐fold on average, but their assessed value have increased by a factor of only about 2.4.

While it is unlikely that many high‐value commercial properties have avoided reassessment through the entire life of Proposition 13, significant gaps between assessed and market value have emerged over shorter periods: between 2012 and 2022 alone, California property prices more than doubled (it should be noted that I am using a residential price index for these value increases; the changes in commercial property valuations are likely to be different).

To reasonably estimate the potential impact of underassessments, it would be necessary to review a sample of local properties. San Francisco’s City Controller is performing such an analysis but the results have yet to be published.

While no other state has Proposition 13, there can still be variances between assessed and market valuations outside of California. For example, a Georgia property assessor reviewed a sample of ten commercial properties and found that, on average, they were assessed at 40% below market value (his findings were published in a paywalled edition of Fair & Equitable, the magazine of the International Association of Assessing Officers).

3. Reassessment Timing

Just as assessments may not reflect market values on the way up, they may also lag declining resale values. But this is less affect is less likely to persist given the incentive that property owners have to minimize their property tax liabilities.

In California, property owners can ask their assessor for a reduction, and, if not satisfied, they can appeal the assessor’s decision to a county board. San Francisco’s Assessment Appeals Board has an active docket of appeals cases at the moment, with some filers requesting assessment reductions of more than 50%. In one extreme case, the owner of the Westin St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco’s Union Square is seeking a 90% reduction in its assessed valuation.

Owners of commercial real estate may hesitate to seek downward reassessments if they are marketing their properties since potential buyers might use the lower assessment as a basis for negotiating a sales price. And, in California, at least, retroactive reassessments are not possible. So, in some cases, a commercial property may be assessed above market value at least during the current tax year.

Conclusion

Although San Francisco may be considered ground zero for the commercial property collapse, the budgetary impact has been limited this far. The city’s FY 2022–23 revenues are running just 1% below prior year levels and the city is forecasting small increases for the next five fiscal years. That said, these are nominal amounts, and it is fair to conclude that San Francisco’s projected revenues are expected to grow at or below the rate of inflation and are significantly underperforming recent growth rates.

San Francisco is receiving some protection from undervaluation before the pandemic and revenue source diversification. That said, the city’s unique challenges may also impact its sales tax and hotel room tax collections as well as its property tax revenues.

For other jurisdictions, results can be expected to vary. Blanket nationwide assessments may well prove to be a poor substitute for an in‐depth look at each city’s and county’s unique characteristics.

Colorado: Record number of Coloradans protest soaring property tax valuations

Tens of thousands of Coloradans are protesting soaring property valuations that threaten to take out a lot more from people’s pockets than in previous tax years. The sharp rise in protests also means a significant increase in the workload for county assessors and their staffers and, later, for county commissioners and district courts that ultimately have the final say on how much tax liability each property owner faces.

In Arapahoe County, the commissioners extended the deadline to send “notices of determination” — the assessor’s initial response to the tax protests — to Aug. 15, instead of June 30. The county saw a nearly 600% increase in protests this year compared to 2021, the last time property values were appraised for taxing purposes.

Unlike some states, Colorado does not cap the property valuation in determining tax liability, which means a 40% increase in market valuation translates to roughly the same amount in tax valuation increase, with some adjustments for mill levy hikes or decreases made by local jurisdictions and an assessment ratio decrease adopted by the state.

The soaring valuations were expected, following the red-hot market of 2021 and early 2022. Consequently, valuation for a median residential house rose by 33% in the City and County of Denver, 42% in Arapahoe County and 47% in Douglas County. Indeed, all nine metro area counties showed double-digit increases hovering near the 40% mark. Denver and Boulder showed the sharpest rise in valuations for apartments at 45% and 44%, respectively. Reappraisal of property values occur every two years, and next year’s property tax liability would reflect increases in market value by June 2022. This means the new numbers tax collectors will use next year will register the sizable runup in values, reflecting the appreciation through the market’s peak in spring 2022 but little or none of any drop-off in values as the market cooled later in the year.

Anders Nelson, the spokesperson for Arapahoe County, said the protests typically come from residents who do not believe their property is worth what the valuation was determined to be. “Normally, the resident feels the value is too high and wants to get it lowered so taxes are lower,” Anders said, who noted there are several opportunities for residents to appeal the valuations.

Brenda Dones, the assessor for Weld County and president of the Colorado Assessors’ Association, explained the conundrum property owners find themselves in, particularly if they had hoped that the more recent, calmer market would help them avoid paying a bigger tax liability. Dones noted that the window to make the initial appeals already closed, and property owners are now waiting for the determinations from the assessors’ offices. “When they receive the decision, I encourage them to try to understand why the property value was adjusted or denied,” Dones said. For tax years 2023 and 2024, the valuation date is June 30, 2022. “Many sales occurred during those two years, and assessors are required to adjust those sale prices for economic changes in the market up until June 30, 2022. In most markets, properties that sold in 2021 were selling for more in June 2022. So, sales prices had to be adjusted to capture that appreciation,” she said. “We are already 12 months past the valuation date and current sale prices might be lower than the value set as of June 30, 2022. However, assessors are barred from considering those sales until the next revaluation in 2025,” she said. “If, at that time, sales prices are lower then property values will be adjusted to reflect those economics.”

Dones said that, if property owners considered these points and they still believe the valuation is wrong, they can file another appeal with the County Board of Equalization. She said they will have a higher chance of succeeding if they provide economic information, ideally sales, that occurred in the two to three months prior to June 30, 2022. Those sales, the assessor said, would be close to the valuation date and so most of the appreciation would already be captured in the sale price. The sales could then be adjusted for differences in characteristics to estimate the value, she said, adding, “This is just like an appraisal to get a mortgage.”

Dones added: “Property owners should also know that the property value is only one piece of the property tax formula. Property owners can also talk with their legislators about the assessment rates and their local tax districts (city, county, fire, etc.) about whether mill levies should be adjusted prior to the taxes being calculated.”

Democrats in the General Assembly sought to offer tax relief by taking a portion of the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights surplus, which pays for TABOR refunds, and divert it for at least 10 years to homeowners and commercial property. They also equalized the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights refunds at $661 per person or $1,322 for joint filers, a one-time change from the current system that bases the TABOR refund on income levels. Voters will have the opportunity to reject or approve the proposal in November. Already, battle lines are forming and both sides have begun to pitch narratives that will likely play out during the campaign.

Delaware: Recurring property tax assessments could become norm for Delaware, if governor approves

The Delaware General Assembly has passed legislation that would make property tax reassessments a regularly-occurring aspect of taxation in the First State. Supporters say regularly-occurring property tax reassessments are necessary to ensure property owners are paying taxes fairly based on the actual value of their property and to fix funding disparities among school districts, which receive significant funding from property taxes. On Tuesday, the Delaware Senate quickly passed legislation to mandate the state’s three counties reassess the valuations used for property tax calculation every five years. The change is something that has been debated and failed to pass through the Delaware General Assembly for decades. The bill now awaits the signature of Gov. John Carney. A spokesperson for the governor did not immediately indicate whether he will sign the legislation, which passed the Delaware Senate with 17 votes in favor, two against and two members absent.

Here’s a breakdown of why the issue is important and why this push is happening now:

So, what is reassessment?

An individual’s county, city and school tax bills are calculated using a tax rate that is local to the school district, city (if applicable) and county to where one’s property is located. That rate is the combined taxable value of that property to calculate one’s property tax bills. Reassessment is the process of making that taxable value reflect something closer to the property’s actual market value, which fluctuates over time. County governments are responsible for conducting those valuations.

What would the new property tax legislation do?

House Bill 62 would force the counties to reassess property values used for tax calculations every five years so that those valuations more closely reflect the property’s “current fair market value.”

Why would you do that?

When property valuations are not updated, the value used to calculate tax bills drifts away from what the property is actually worth. And that drift isn’t uniform. Over the years, different areas and different types of property appreciate value faster than others. If the values used for tax calculations are not updated, some people are paying bills calculated using values that are far departed from the actual value of the property. Outside of Delaware, most governments regularly reassess taxes to maintain fairness in the taxing values. Delaware’s three counties have not done so in decades, but are right now because a judge is making them.

Court case prompts reassessment

The current reassessment is occurring because of a court ruling that found the state’s outdated property tax valuations to be unconstitutional. There hadn’t been an update of those valuations since the ’70s in Sussex County and the ’80s in Kent and New Castle counties. The ruling did not mandate regular reassessments however, which is why lawmakers have passed the legislation requiring reassessment every five years.

Reassessment already underway

Each of the state’s three counties is reassessing property values to current fair market value for the first time in decades. That includes going door to door to put eyes on each taxable property. Here’s a breakdown of relevant timelines for each of the three counties:

- New Castle County: Tentative valuation notices should go out in the fall of next year. These values will first be used to calculate new tax bills starting with the 2025 tax year.

- Kent County: Tentative valuation notices should go out later this fall. Tentative tax assessment rolls will be finalized in February 2024.

- Sussex County: Tentative valuation notices should go out in the fall of next year. New assessed values will go into effect in 2025.

The ongoing process includes a provision to allow appeals of reworked property tax assessments. Tyler Technologies is the contractor conducting reassessments and has set up websites for each county with pertinent information on the schedule for home-visit surveys, public meetings on the issue and other topics relevant to reassessment.

EUROPE

France: New property tax declaration sparks fury among homeowners and bureaucrats

If you’ve been having problems with the new French property tax declaration then you are not alone – the tax office has been inundated with complaints about the system, and unions representing tax office staff are also furious. The one-off déclaration d’occupation is a new tax requirement this year, and must be completed by all property-owners, informing the tax office whether their property is a main residence or a second home. The reason for this is the recent abolition of the taxe d’habitation (householders’ tax) on all properties, with the exception of second homes. The tax office requires an up-to-date record of whether a property is a main residence or a second home, so that correct tax bills can be sent out in the autumn. It must be completed by all property-owners in France, and it is an online-only procedure, completed via the tax website impots.gouv.fr.

The deadline was initially Friday, June 30th – that has already been extended until July 31st and may have to be extended again after tax offices reported being inundated with complaints and problems. A single day – June 16th – recorded 94,000 calls to the tax helpline, almost all of them concerning the property tax declaration. The biggest cause of complaints – according to unions representing the stressed-out staff at tax offices – were the lack of a paper option for the form and the lack of a receipt once it is filed online, so people cannot be sure that their form was processed correctly.

The Local has also received a high number of queries from property-owners in France, with second-home owners most commonly experiencing problems. The declaration is filed via the ‘personal account’ on the tax office website – something which residents in France have in order to file their annual tax returns but many second-home owners who live abroad do not. Creating the account has proved difficult for many, with requests for in-person ID checks for many second-home owners.

France: We were over-optimistic about new property form, says French tax chief

The head of the central tax authority admits to long queues and stressful situations for staff, though things are now improving

The head of the French tax service has admitted to having been “over-optimistic” about how well-known the obligation to make a new property declaration was to the public this year. Initially, it was planned that everyone owning residential property in France would have to make a declaration by the end of today (June 30). But last weekend the deadline was extended until the end of July.

Jérôme Fournel, director general of the Direction Générale des Finances Publiques (DGFiP), told BFMTV there had been “unusually long queues” at tax offices and that the “number of in-person and phone contacts shot up”. It comes as the FO union’s financial branch described a “nightmare” situation for staff, sometimes confronted by anxious and upset people who have turned aggressive at times. He admitted that the DGFiP had “to some extent overestimated how well-known the declaration obligation is”, despite having sent out millions of emails to people whose contact details they held and run a communications campaign.

More people than expected ended up leaving the process to the last minute, he said. However, the rush does now seem to be calming down, and they are hopeful that almost everyone will have declared by the new deadline on July 31. Around 63% of declarations have been completed so far, he added.

The main purpose of the declaration, which for most people should be done online in your personal space on the tax website, is to check the usage of properties. This is, in particular, so that tax offices are sure of having up-to-date information on whether houses and flats are used as main or second homes. This issue has become more important this year as no main homes are now subject to the taxe d’habitation residential tax, whereas second homes, including homes of non-residents, remain liable to this tax.

Authors:

- Paul Sanderson, President | psanderson[at]ipti.org

- Jerry Grad, Chief Executive Officer | jgrad[at]ipti.org

Compliments of the International Property Tax Institute (IPTI) – a member of the EACCNY.

![European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources](https://eaccny.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/eaccny-logo.png)