Since the start of the invasion of Ukraine, the EU has imposed 11 rounds of ever-tighter sanctions against Russia. Some people claim these sanctions have not worked. This is simply not true. Within a year, they have already limited Moscow’s options considerably causing financial strain, cutting the country from key markets and significantly degrading Russia’s industrial and technological capacity. To stop the war, we need to stay the course.

Our restrictive measures, to use the technically correct term, are unprecedented in their scope, focusing on key sectors of the Russian economy that are crucial to Moscow’s war effort. In addition, the EU has also imposed travel bans and asset freezes on more than 1,500 individuals and almost 250 entities.

Hard tangible effects across Russia’s economy

These measures are producing hard, tangible effects across Russia’s economy, despite the huge oil and gas revenues Russia used as a buffer in the first year of the invasion. And their effects will intensify over time, as the measures have a long-term impact on Russia’s budget, and its industrial and technological base.

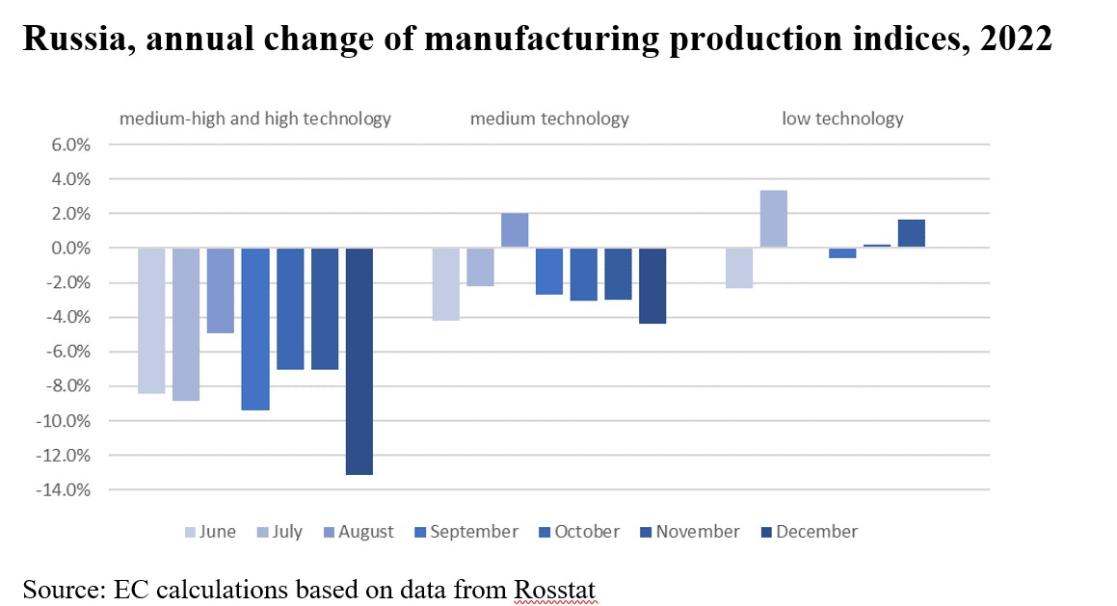

The Russian economy contracted in 2022 by 2.1%. Manufacturing in particular – growing steadily before the invasion – was down 6% at the end of 2022, with high and medium-high technology manufacturing recording a 13% annual loss. The production of motor vehicles was down 48% year-on-year, other transport equipment by 13% and computer, electronic and optical production by 8% while retail trade was 10% lower and wholesale trade 17%.

The outlook for 2023 remains bleak

And the outlook for 2023 remains bleak. According to the latest OECD report, Russia’s GDP is foreseen to shrink by up to 2.5%. All the components of Russian private demand, including private investment and consumption, remain depressed. Only public expenditure related to the war effort, i.e. defence spending, is up.

Russian carriers are no longer able to fly to, from and over EU territory. Most modern aircraft operated by Russian carriers are dependent on European and American spare parts and technical assistance, which have been banned. The ban on new investment across the energy sector and export restrictions on technology and services for the energy industry have undermined the viability of Russian companies. The credit rating agency Moody’s has already downgraded 95 Russian firms (including most energy companies).

Source: European Commission

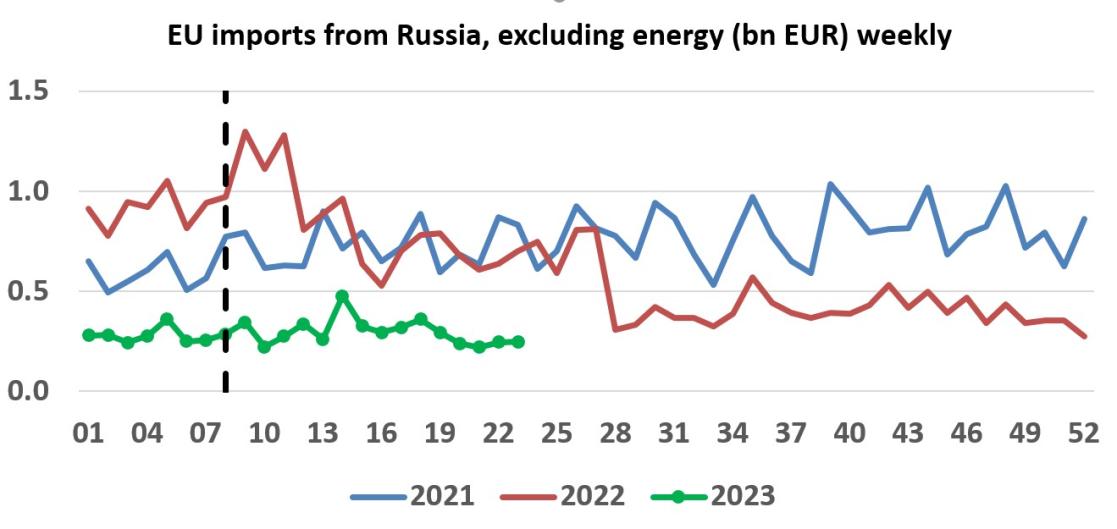

Compared to 2021, 58% of total EU imports from Russia were already cut off in 2022 – an unprecedented decoupling. Non-energy imports from Russia have fallen close to 60%, with the most visible drops for iron and steel, precious metals and wood. This movement is accelerating: the decline in imports of non-energy goods is above 75% for the first quarter of 2023, and the fall is even greater for energy goods, at minus 80%.

Source: European Commission

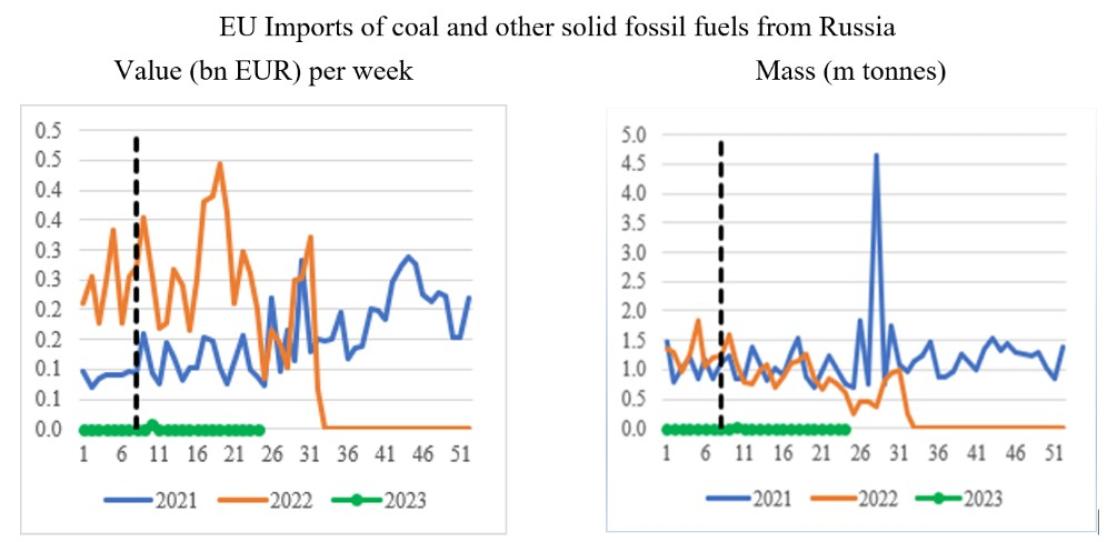

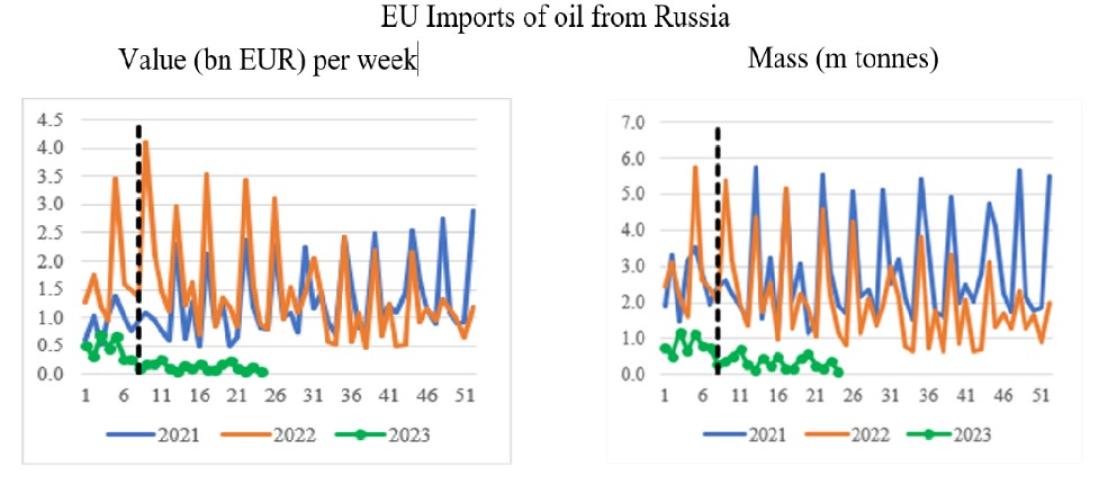

Since 10 August 2022, EU imports of Russian coal have stopped completely affecting around one fourth of all Russian coal exports. The G7+ energy sanctions on oil have proven effective. The price of Russian oil has fallen since the start of the EU embargo and G7+ oil price caps. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports an average Russian crude oil export price at around $ 60/barrel in April 2023, a $ 24/barrel discount compared to the global oil price. The IEA also estimates that total Russian oil revenues are down 27% from a year before. At the same time, as was intended by the G7+ countries, despite falling exports to the EU, the overall volume of Russian global oil exports held up relatively well, helping to keep global markets stable. On gas, Russia’s own decision to cut flows and the EU’s strong diversification efforts resulted in a dramatic fall in volumes. Despite this, we have managed to get sufficient gas stocks ahead of next winter.

Source: European Commission

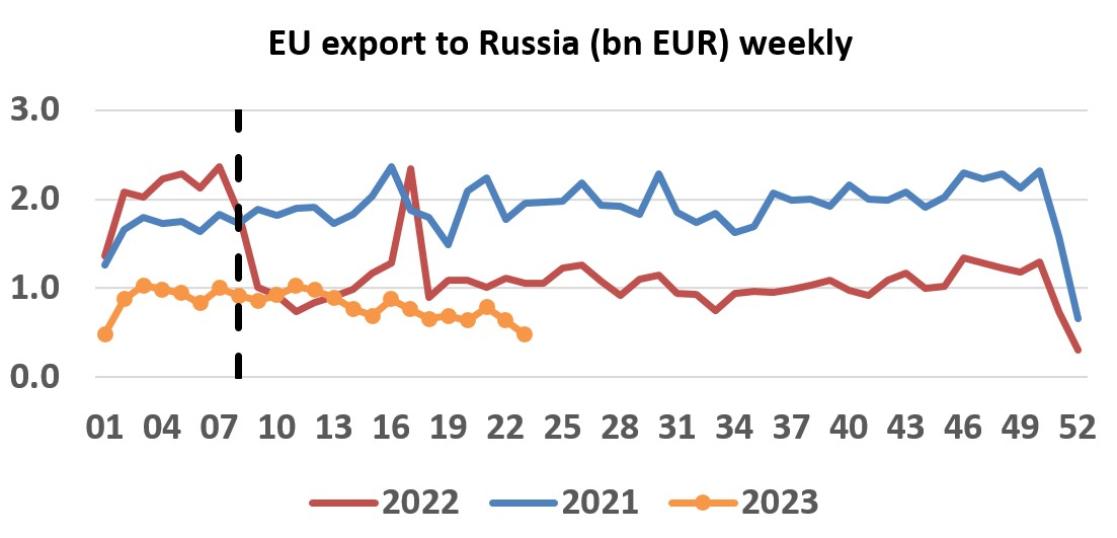

On the export side, restrictive measures to date cover around 54% of 2021 EU exports, targeting key capital and intermediate goods where Russia has a high dependency on supplies from the EU, United Kingdom, United States and Japan. Overall EU exports of goods were 52% below the annual average before the war in 2022.

Source: European Commission

EU exports on dual-use items and advanced technologies, which are essential to produce the equipment and weapons used by Russia to wage its war, dropped by 78% in 2022 compared to 2019-2021. EU trade restrictions so far exclude products, other than luxury goods, primarily intended for private consumption like pharmaceuticals, food, medical devices and some specific agricultural machinery. However, even in many areas that are not under sanctions, many EU companies have stopped trading with Russia and EU exports in non-sanctioned sectors are down by over 10% on average.

Russia’s war of aggression is the root cause of the global food insecurity

At the same time, the EU is also ensuring that its sanctions do not unduly affect trade in sectors, such as food and energy security, for third countries around the globe, in particular the least developed ones. Specific exemptions and guidance have been established to that effect. Russia’s war of aggression is the root cause of the global supply shock in the areas of food and related items by invading Ukraine, one of the main breadbasket of the world. The fact that Russia decided to exit the Black Sea Grain Initiative last July, attacking since then massively silos and Ukrainian ports, risks to aggravate again the global food security situation in coming months. The EU will continue to counter Russia’s false narrative on these issues and work closely with partners that are negatively affected by Russia’s actions to mitigate these effects.

Russia had an important budgetary surplus for the first half of 2022 due to high oil and gas prices but it has been erased in subsequent months, with the federal budget ending in a deficit in 2022. The fiscal situation is expected to worsen. January-April figures for 2023 showed Russia’s oil and gas federal budget revenues, representing 45 % of Russia’s budget in 2022, dropping 52%. The government is trying to address the revenue slump by extracting high dividends from state-owned enterprises and levying additional taxes on large businesses but these have their own costs and are unlikely to plug the growing fiscal deficit.

While the Russian government still has fiscal space with a public debt that stood at 17% of GDP at the end of 2021 and accumulated assets in the National Wealth Fund (NWF) that remain sizeable (as of April 2023, $ 154 billion, or 7.9% of GDP), it squeezed productive and social spending. In 2023, nearly a third of the federal budget is expected to be spent on defence and domestic security while funding for schools, hospitals and roads is slashed further.

In 2023, the current account surplus has decreased dramatically as import volumes recovered due to the increase in more costly substitution imports. At the same time, sanctions on Russian exports and the G7 price caps effectively reduced the income from Russia’s main exports. Russia has turned increasingly to the yuan as a means of transaction and a store of value – a currency with non-transparent capital controls. This in turn has increased the costs of doing financial transactions between Russia and the outside world.

Benefitting from measures like banning non-residents from transacting in the financial markets and a record current account surplus due to high commodity prices, the rouble appreciated against the euro following the start of the war. The exchange rate thus very much reflected the decoupling of the Russian economy from the global one. With the degradation of the current account, the rouble depreciated again in the second half of 2022 and has further weakened massively in 2023. It is now at its weakest for many years, trading at lower levels than during the pandemic. To try to halt this fall, the Russian Central Bank had to raise sharply interest rates from 7.5% in July to 12% on 15 August. This high interest rate will put an even greater brake on economic activity in Russia in coming months.

Large parts of the reserves of the Central Bank of Russia have been immobilised in the EU and other countries (of the € 300 billion assets immobilised, € 207 billion are in the EU). The EU, together with partners, is working to find ways to use revenues of the immobilised assets of the Russian central bank to support Ukraine’s reconstruction and for the purposes of reparation, while ensuring this is done in accordance with EU and international law.

Russia is trying to counter EU measures

Meanwhile, Russia is trying to counter EU measures. It is turning to non-sanctioning countries in search of technology and intermediate products. Russia’s overall imports fell post-invasion by around 18% from April to November 2022 compared to the same period of 2021. After this slump, Russia’s imports from China increased by 27%, in particular for machinery, electrical equipment and cars. Russia has also been introducing measures that have made it more difficult and costly for foreign companies to leave the Russian market.

While it is questionable if others can fully fill the space left by sanctioned EU goods, it underlines the need to act more firmly against the circumvention of EU sanctions. To this end, we are stepping up our engagement with key third countries, urging them to closely monitor and act against trade in EU sanctioned goods, particularly those found on the battlefield in Ukraine. In this regard, the EU Special Envoy David O’Sullivan will play an important role.

Within a year, sanctions have already limited Moscow’s political and economic options, causing financial strain, cutting the country from key markets, increasing the costs of trading and significantly degrading Russia’s industrial capacity. Looking at Russia’s long-term growth prospects, the technological degradation and the exit of foreign companies will hamper investment and productivity growth for years. The labour market situation was not favourable before the invasion due to Russia’s demographics. Mass conscription has worsened it further and the growing lack of opportunities exacerbates the brain drain from Russia. In short: Russia’s decision to attack Ukraine has obviously pushed the Russian economy towards isolation and decline.

Compliments of the European Commission.

![European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources](https://eaccny.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/eaccny-logo.png)